THE EFFECT OF GLOBALISATION ON NOLLYWOOD AND SOUTH KOREAN CINEMA

- week four

- Aug 24, 2017

- 3 min read

Nollywood and the Korean wave are two examples of the profound effects of globalisation on the entertainment industry. Nollywood is the Nigerian film industry while the Korean wave is the term used for the growing global popularity of South Korean cinema.

In South Korea, globalisation has created a flow of prosperity and helped to build the now seventh largest film market in the world. Online dissemination of the films through imagined communities and the physical sale of DVDs has increased the access to the industry exponentially. As a result, the films are now generating profit outside of Korea that can be used within the industry to create a larger number of “impressive looking” (Ryoo 2009, p. 139) films or introduced into the national economy. Tight government legislation surrounding plagiarism and access to the films, and heightened global competition from international film festivals have motivated the industry to generate “more films, and faster and less predictable, even unique, storylines that are more clever and aggressive” (Ryoo 2009, p. 142), thus boosting the profits for the industry. As an already reasonably wealthy country, South Korea’s capacity for high production values was one of the main aspects of the films’ critical and commercial success because it was a factor that translated well internationally as it isn’t directly related to language or cultural values. In such a diverse era where cultures are continuously shifting and evolving, a singular self is simply not as realistic form of being, and thus, the hybridization discourse is a much more effective approach to producing films. Hybridization is also a prominent means of cultural production and consumption in both a local and global context, with locals encouraged to “rediscover the local that they have… forgotten in their drive towards Western-imposed modernization” (Shim, 2006; Spivak, 1988, cited in Ryoo 2009, p. 143). Therefore, for South Korea, globalisation of media and communications, mixed with the increasing reality of cultural hybridity has driven the Korean wave.

In contrast to South Korea, globalisation has provided the technology and materials to produce films in Nigeria, rather than the means to spread them. Nollywood started to flourish in the late 20th century when technology such as video cameras became available at cheap prices. This fundamental element of film production would not have been accessible if it weren’t for international transport and the globalisation of trade. Globalisation has also aided in the dissemination of films to the local audience, but also the world, with a variety of films being included in international film festivals from the beginning of the 21st century.

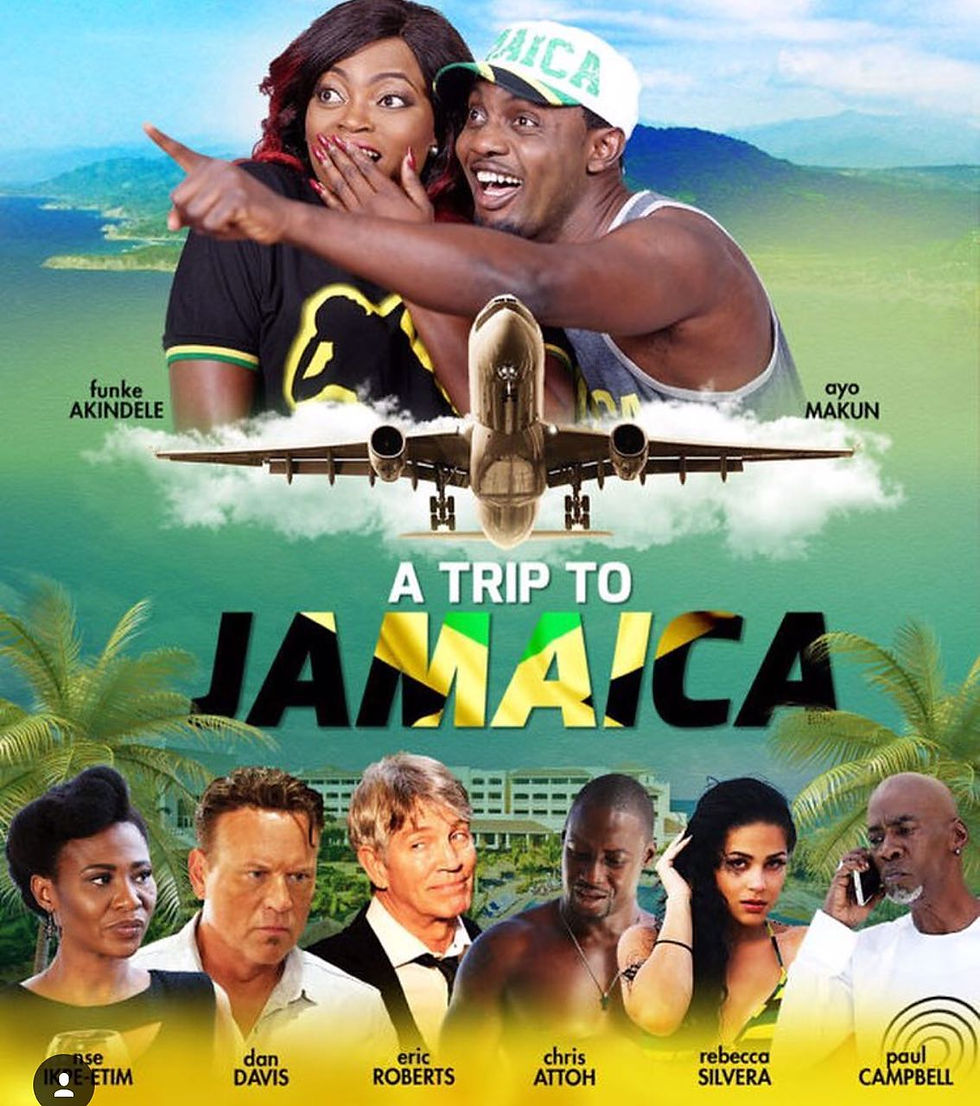

Despite Nigeria’s status as a developing country, the (relatively) low production values have not hindered the success of the films locally. At variance with Hollywood and arguably South Korean cinema, Nollywood films “look inward and not outward,” according to Prof. Onookome Okome (2007, p. 1). The films refer directly to Nigerian culture, lifestyle and events, with the success of the industry deriving from the stories and subject matter of the films rather than the mode of production. Okome writes, “it is not the medium… that matter[s] to the people who consume Nollywood. The focus is on the stories.” (2007, p. 19). ‘A Trip to Nigeria’ (2016), the second highest grossing film in Nigerian history, exemplifies how the global critical response is separate to the content of the film. The movie received largely negative reviews, but appealed to the Nigerian audience because the Nigerian cast members were relatable, also providing the populace with a way of ‘leaving’ Nigeria.

There are some anti-globalist aspects of Nollywood as the films aren’t shown in cinemas or have the extensive process of promotion and distribution, but even despite the lesser cinematic quality and the inherently Nigerian subject matter, the industry can still be considered global. The honesty and “acute notion of locality” has made it an “unprecedented” cinematic expression of Nigeria and Africa (Khorana 2017) for the world, and because the industry has adopted global techniques and equipment, it is still a product of globalisation.

Trip to Jamaica, 2016

Khorana, S 2017, ‘Globalisation, Media Flows and Saturation Coverage’, lecture, BCM111, University of Wollongong, delivered 1 August.

Ryoo, W 2009, ‘Globalisation, or the logic of cultural hybridization: the case of the Korean wave’, Asian Journal of Communication, pp. 139 – 143.

Okome, O 2007, ‘Nollywood: Spectatorship, Audience, and the Sites of Consumption’, Postcolonial Text, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 1, 19.

Comments